Earlier this year, I went on an 8-day silent Vipassana meditation retreat in Thailand. Below are my diary and sketches I made during the retreat. I hope it can be useful to anyone interested in trying this practice. You can skip to the end of the post to learn about the main changes I have noticed in my every day life after the retreat.

Note: All quotes are from the Alan Watts book The Way of Zen.

* * *

DAY 1: FLOATING ANGELS

I’ve just arrived to Wat Phra That in Doi Suthep. I was told to eat something before coming here – no food is allowed after 11am. I’m told to change into my white clothes and meet back at the main hall for the meditation demonstration. My room is a small concrete cube in a big white hospital-like building, with only a bed, and a stack of meditation cushions in a corner. The place is surrounded by a gorgeous lush forest.

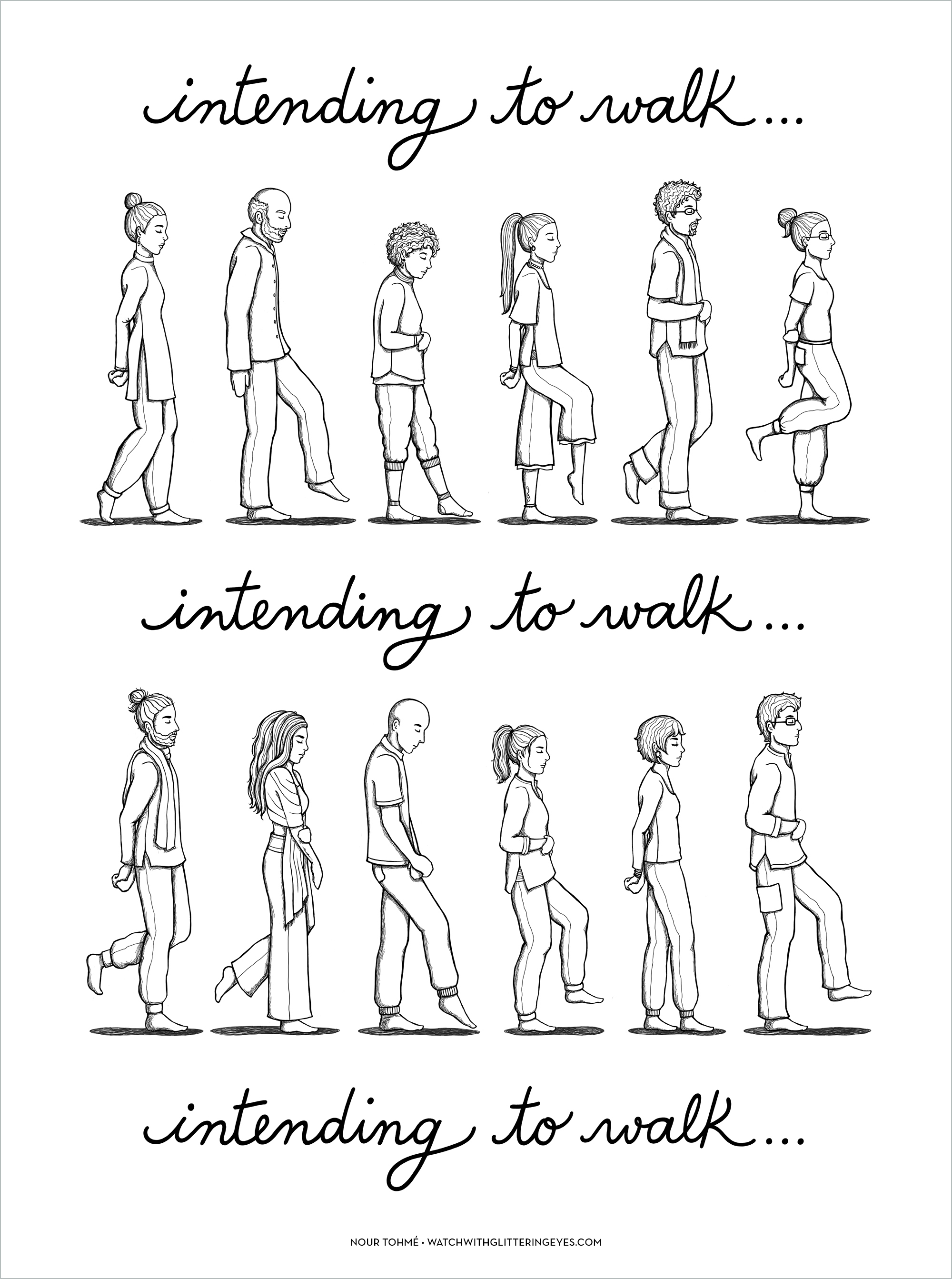

Two other new meditators, a man and a woman, join me in the hall. (*I would later realise that they were a couple, when I would see them always sitting together and trying to communicate without speaking). I call them the “rock n’ roll couple” in my head. They’re both covered in tattoos and have edgy haircuts. A monk demonstrates the walking and sitting meditations that we have to practice during the retreat. He tells us to alternate between 15 minutes of walking and 15 minutes of sitting meditations.

Walking meditation:

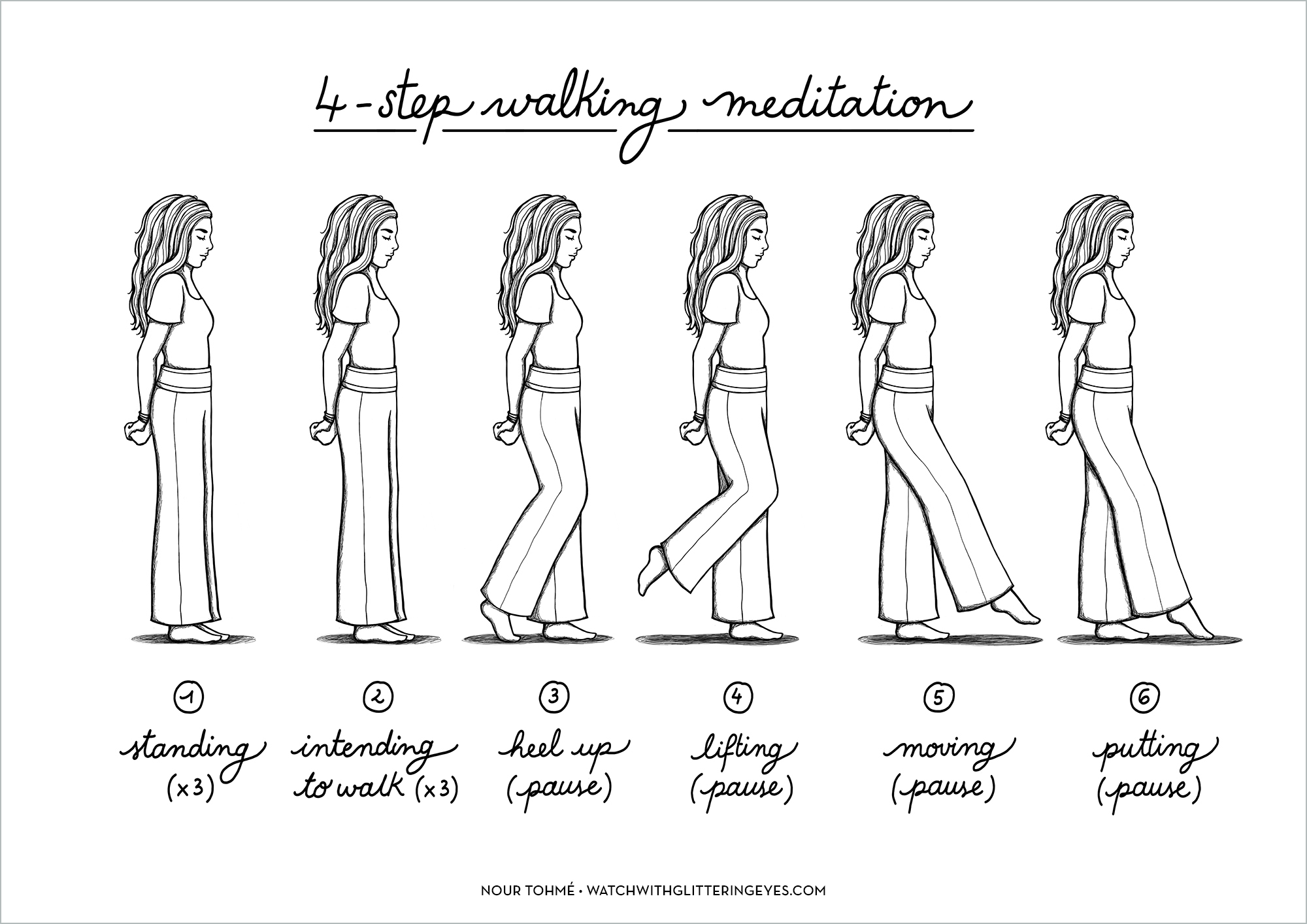

The walking meditation is broken down into phases.

1. Starting in standing position, you mentally “confirm” your standing state by repeating to yourself “Standing, standing, standing”, keeping total awareness on your immobile, standing body.

2. You confirm your intention to start walking, by mentally repeating “Intending to walk, intending to walk, intending to walk”.

3. You start walking by breaking down your steps into 3 movements: lifting the foot, moving it forward, then touching it to the floor, while thinking “Right-go-touch, Left-go-touch”, and so on.

4. Upon reaching the top of the carpet, you confirm your intention to stop walking by repeating “Stopping, stopping, stopping”.

5. Before turning around and walking in the opposite direction, you confirm your intention by thinking “Intending to turn, intending to turn, intending to turn”.

6. You repeat the whole process again, beginning with “Standing, standing, standing”.

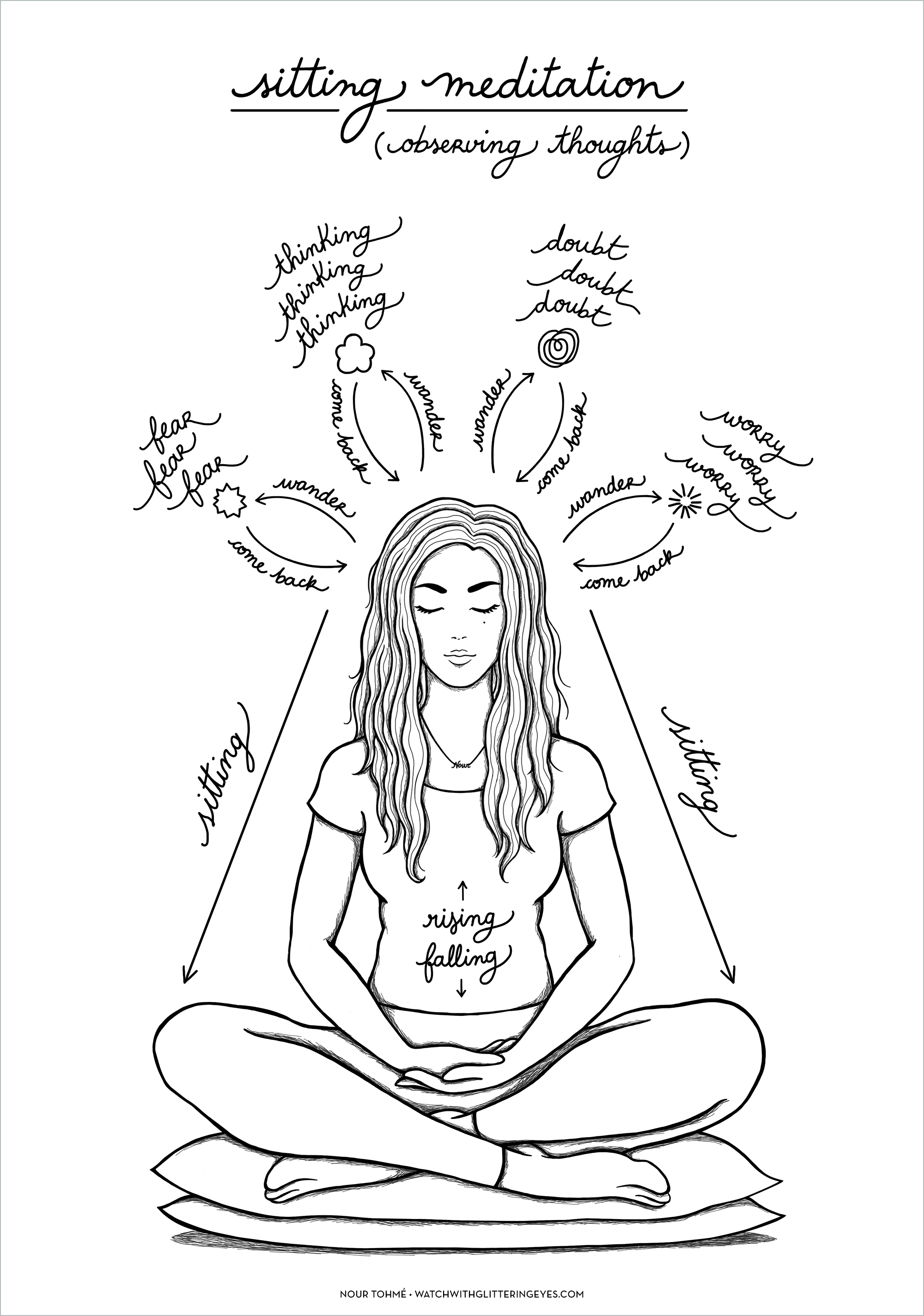

Sitting meditation:

The sitting meditation is done by bringing total awareness to your breath, by focusing on the rising and falling movements of your belly with every inhale and exhale, while mentally repeating to yourself “Rising, falling, rising, falling…”.

Whenever the mind wanders, you gently bring your attention back to the rising and falling of the belly. Lying meditation is performed very similarly while laying down, preferably at night in bed, before falling asleep.

We’re then told to go upstairs to the meditation hall, for afternoon meditation. In a big luminous room, meditators all dressed in white are performing their walking meditations in parallel lines on a series of long thin carpets. It was one of the most beautiful things I had ever seen. Floating angels gliding so gracefully, in slow motion. So slowly that they remain completely immobile for a few seconds, sometimes balancing on one foot. A surreal sight. I had always thought that walking meditations were done at a normal walking pace. Slowly, but still natural. I never imagined they would be this slow, like suspended in time.

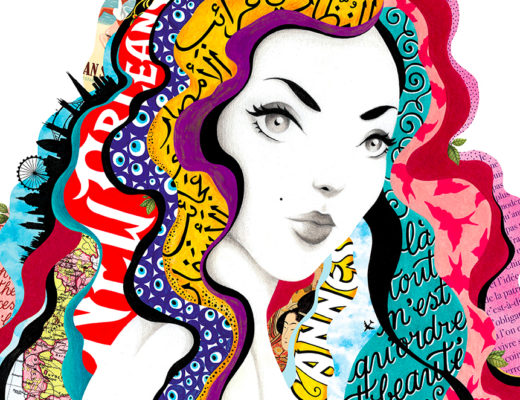

(NOTE: These are portraits of the real people I “met” (+ me!) but never talked to. If you know anyone who was at Doi Suthep meditation center in Chiang Mai end of February/beginning March 2017 and recognize them, please let me know!)

Most meditators seem to be in their 30s and 40s, a few in their 50s and 60s. Marble shrines lie at the end of each carpet, each carrying a Buddha statue, incense, white roses, and pink lamps shaped like lotus flowers. I take a cushion and sit on top of one carpet. I do 15 minutes of sitting meditation. My mind wanders all over the place, but I try my best to bring it back to my belly. Sometimes I get distracted, and start looking around the room. The meditator next to me is a beautiful woman, gliding so gracefully as she walks, with a gentle serene expression on her face. Her grace somehow calms my agitated mind and helps me get back to focusing on my breath.

I then stand up to start my walking meditation. Standing, standing, standing. Intending to walk, intending to walk, intending to walk. I start walking, slowly, observing my moving feet. I find it slightly easier than the sitting meditation. Focusing on the movement of my feet felt better than focusing on my belly. It took me 15 minutes to walk to the top of the carpet and back, a distance that would be walked in under 5 seconds at a normal pace. I sit again, and start another sitting meditation. With difficulty, I finish, put away my cushion and try to get out of the room, but can’t get the massive door to open. The graceful lady comes over and helps me, smiling at me gently.

At 4, the new meditators are told to meet back at the hall for the opening ceremony. We meet the monk who will be our teacher during the retreat. We sit in front of him, and another monk gives each one of us a booklet with Buddhist chants in Pali, and a tray filled with yellow flowers to offer to the monk. Aside from not speaking, we vow to abstain from killing any living being (no eating animals is allowed here), from stealing, from sexual activity, from alcohol or smoking, from eating after midday, from wearing perfume, and from using electronics.

We chant together, then the monk tells us about the benefits of Vipassana meditation. Training and knowing our own minds, he says, helps us balance our energy and put out the best of it into the world. By knowing our own mind, we can better know and understand others. By training the mind to focus on the body, on the present moment, instead of thinking about the future and the past – and all the feelings and worries associated with those – we can develop a sense of balance and inner peace. Learning to observe our own mind helps us come out of the “auto-pilot” mode most of us live in, and develop a better understanding of ourselves.

At 6, all the meditators meet in the hall for an hour of chanting with the monk. There’s a translation at the end of the booklet, but I have no time to read it while I try to keep up with the monk and the others’ chanting. Even though I do not understand a single word, the chanting is soothing, and our voices in unison sound beautiful. The monk then tells us some stories about the Buddha, and we all go upstairs to the meditation hall again, for evening meditation.

Right-go-touch, left-go-touch. While I walk, I can’t help but get distracted and watch the others, watch how they’re walking, their particularities. Some walk with their eyes closed, with a slight frown on their face. Some take long, very slow steps. Some take tiny, more frequent steps. Some clasp their hands in the front, others in the back. Some flex their feet in exaggerated motions. Others point their toes like dancers. Some elongate their bodies, while others bend their knees.

I start wondering who these people are, where they’re from, what they’re like in real life, what they usually do – you know, besides walking in slow motion. I notice an older woman with a melancholic face, meditating on a chair instead of sitting on the floor. I wonder what’s making her so sad, what she must be going through.

NO Nour, focus! I observe my mind wandering, and quickly get back to my steps. Intending to walk, intending to walk, intending to walk. Right-go-touch, left-go-touch. I keep alternating standing and sitting meditations. I meditate for an hour. I’ve never meditated this long in my life.

I go back to my room, and lie on my bed. I’m not sleepy, so I start reading. I’m cheating, I know. But it’s a book about Buddhism. That can’t be breaking the rules too much, right? Alan Watts’ The Way of Zen. I try a lying meditation before falling asleep. I focus on my belly. Rising, falling, rising, falling. I feel very calm and peaceful.

And hungry.

DAY 2: MONKEY MIND

It’s 5 am. Alarms start going off as we all wake up and get ready for Dhamma talk at 5:30. We all sit on the floor in front of the monk, except for the melancholic lady and another older man who sit on chairs. The monk talks to us about the meaning of true happiness, and that it is achieved by overcoming suffering, or “dukkha”. I just read about dukkha in the Alan Watts book last night. It’s the first of the Four Noble Truths in Buddhism.

“The First Truth is concerned with the problematic word dukkha, loosely translatable as “suffering”, and which designates the great disease of the world for which the Buddha’s method (dharma) is the cure. Birth is dukkha, decay is dukkha, sickness is dukkha, death is dukkha, so also are sorrow and grief….To be bound with things which we dislike, and to be parted from things which we like, these also are dukkha. Not to get what one desires, this also is dukkha. In a word, this body, this fivefold aggregation based on clutching (trishna), this is dukkha. This, however, cannot quite be compressed into the sweeping assertion that “life is suffering”. The point is rather that life as we usually live it is suffering – or, more exactly, is bedeviled by the peculiar frustration which comes from attempting the impossible. Perhaps, then, “frustration” is the best equivalent for dukkha, even though the word is the simple antonym of sukha, which means “pleasant” or “sweet”. ”

The monk says that happiness is attained by developing a freedom from the material world, or “non-attachment”, which can be achieved by practicing “samadhi”. Samadhi is a state of intense concentration or absorption of consciousness induced by complete meditation. Happiness is also attained through liberation from the ego, which can be achieved by practicing Vipassana, or “insight meditation”. “Vipassana” means to “see things as they really are”. This method uses mindfulness of breathing, continued close attention to sensation, combined with the contemplation of impermanence and self-observation to pave the way for self-transformation, and to gain insight into the true nature of reality.

During the Dhamma talk, the melancholic lady doesn’t seem to be feeling well and falls off her chair. The graceful lady rushes to her side and helps her up.

A very loud bell goes off at 7am to call us for breakfast, and dogs start barking all around the center. We each get a small bowl of rice noodles and tea. There are around 6 tables in the dining hall, and we sit in small groups, eating quietly. I take a seat and look hesitantly at my bowl. I’ve never had noodles for breakfast before. I force myself to eat, dreaming of fruits and a cup of coffee.

After breakfast, I go back upstairs to meditate again. We’re allowed to use our phones as a timer for meditation rounds. One meditator’s timer sound is a cat meowing. I try hard not to laugh whenever it goes off.

The sitting meditation hurts me back, and I’m unable to focus on my belly. My mind keeps drifting between the pain and random things. While I walk, my eyes still sometimes get distracted by the other meditators as I observe their paces. I start wondering about my own walking, how my body is behaving while I meditate. I’m definitely a front-hand-clasper and a pointy-toe-walker. Stop Nour, FOCUS. I shake my head and let my self-centered thought go, with a slight bit of shame.

I expect to get bored, but I don’t. I enjoy the meditation, although my mind wanders and I struggle to stay in a meditative state for too long. Mostly, I’m wondering how this technique links to the concept of anatta – or “no-self” – and the ego. I still don’t fully understand the relation. In what way does practicing this meditation help to detach from the ego, or become a better person? How does it help with wisdom and compassion in everyday life? Also, how can I possibly develop “non-attachment” to my body – which is part of the “material world” – while having to be completely aware of it and observing it for hours and hours on end? I still have so many questions.

The bell goes off again to call us for lunch at 11am. White rice, tofu and some cabbage. I have no appetite, but knowing that I won’t be eating again till the next morning, I force myself. I try to eat mindfully while feeling gratitude for every bite. The graceful lady and the melancholic lady sit together again, like at breakfast. I sit alone at a table, and soon the old man joins me, as well as another man. A young man who appears to be very shy. I call him “the nice man who looks down at his feet”. There’s a little “mini-market” in the dining room where they sell basic toiletries and snacks. The old man buys himself a pack of Oreos, opens it and kindly offers me one. I smile at him and politely shake my head no. I had noticed him the last 2 days, and seen him walk in the most delicate way. He is the only one who doesn’t clasp his hands in front or behind him, but rather leaves them hovering on his sides. Kind of like a tightrope walker.

Some people buy themselves snacks after lunch, to have them later in the day when no more food is allowed. I decide to resist. I’m going to try not to give in to the hunger, to fully live the experience like the monks do.

There is a white board in the dining hall with the daily schedule and the current number of meditators. We’re 11 men and 12 women right now.

I struggle with my sitting and walking meditations today, so I try to meditate on the balcony of the meditation hall, in the sunshine. On the windows, people have written messages with their fingers, in the dust. Mostly positive spiritual messages. But the best one says “I am the batman”.

At 1pm, we all have to report to the monk. He gives each of us instructions for the next “level” of meditation. Instead of “Right-go-touch, Left go touch”, today it’s “Lifting-putting”. Lifting the foot in the air, pausing, then putting it down.

He asks me if my first day of meditation was difficult, how much percentage of my focus was on my breath and how much of it was on other thoughts. I say 30%-70%. He says that’s completely normal. Phew.

After chanting, the monk gives us a technique to get better at our meditations: the idea is to try to maintain mindfulness even during the breaks. To be fully aware of the body in the present moment, to always bring the attention back to the body, even while performing mundane tasks during the day. Our body is our home, the home of the mind. If the mind wanders, we can always bring it back to its home.

He says that with mindfulness, a person can get better at solving their own problems. Because they can see them clearer, from a distance, with detachment. Sometimes, when we have a problem, he says, our mind “stays with the problem”, instead of staying with “us”.

I don’t think I’m getting any better at maintaining focus on my breath. But I think I’m getting better at observing my thoughts. My mind still wanders all over the place, but now I can catch it wandering. I can recognize the thoughts and feelings that pop up, “label” them, watch them with a certain detachment, and choose not to engage in them if they’re useless or harmful. I can actively choose not to continue a thought, gently let go of it like a floating cloud, and get back to my breath. What a liberating feeling.

Even though it’s not allowed to read or write or use electronics (and I promised myself I wouldn’t cheat), I can’t help but write down some notes every time I go back to my room. I feel this urge to write down everything I’m learning here, that this information is too important and that I need to record this process, perhaps to look back on it later and study my evolution, or perhaps so it could benefit someone else who might read this someday.

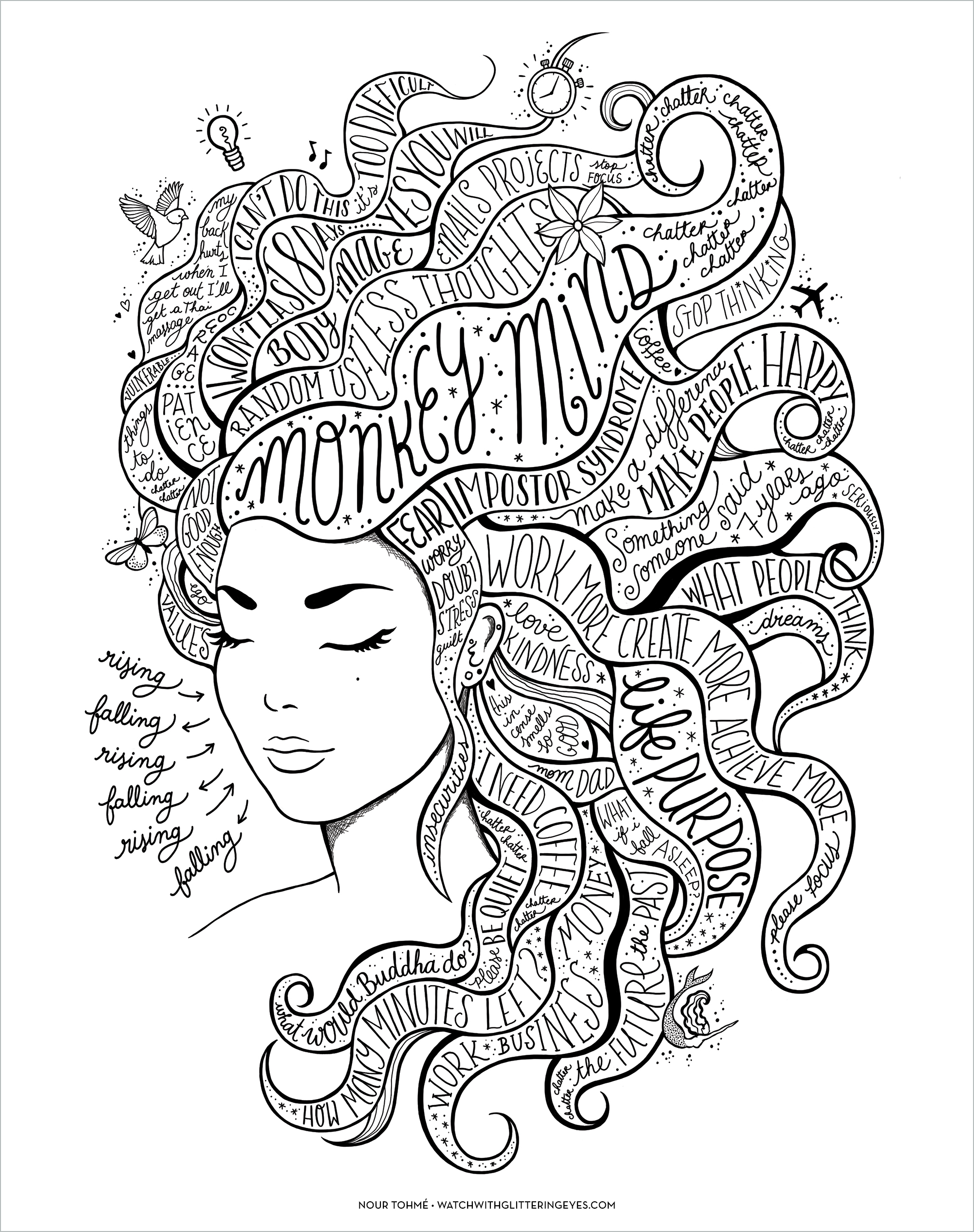

DAY 3: TRISHNA

In today’s Dhamma talk, the monk tells us about the many different techniques of meditation: meditation through sound, meditation through looking at fire, meditation with a mantra, mindfulness meditation through breathing (by focusing either on the nose or on the belly, as we are doing here). What all of these have in common is the deep concentration on one “object”, although this object can take many forms. The monk says that practicing such forms of concentration for a short time during meditation can help improve focus throughout the entire day. When we’re in “autopilot” mode, the monkey mind drains our energy if we let it go on without mindfully putting a stop to it. By meditating and focusing, we can channel our energy and give it power, and we can perform our daily tasks better.

I think I’m starting to better understand the relation between meditation and liberation from the ego. The idea of “no ego” or “no-self” is very central to Buddhism. This whole time, I’ve been trying to understand how this ideal state can be achieved through mindfulness meditation, but I just couldn’t make the link. I’m reading about it in the book now, and it’s finally starting to make sense to me.

“The true Self is non-Self, since any attempt to conceive the Self, believe in the Self, or seek for the Self immediately thrusts it away. […] It is fundamental to every school of Buddhism that there is no ego, no enduring entity which is the constant subject of our changing experiences. For the ego exists in an abstract sense alone, being an abstraction from memory, somewhat like the illusory circle of fire made by a whirling torch.”

In Buddhism, meditation (or dhyana) is composed of smirti or complete recollectedness, and samadhi or contemplation. Smriti and Samadhi are the 7th and 8th steps in the Noble Eightfold path, the Buddha’s guide towards the end of suffering and the path to liberation.

“Smriti (recollectedness), and samadhi (contemplation), constitute the section dealing with the life of meditation, the inner, mental practice of the Buddha’s way. Complete recollectedness is a constant awareness or watching of one’s sensations, feelings, and thoughts – without purpose or comment. It is a total clarity and presence of mind, actively passive, wherein events come and go like reflections in a mirror: nothing is reflected except what is. Through such awareness it is seen that the separation of the thinker from the thought, the knower from the known, the subject from the object, is purely abstract. There is not the mind on the one hand and its experiences on the other: there is just a process of experiencing in which there is nothing to be grasped, as an object, and no one, as a subject, to grasp it. Seen thus, the process of experiencing ceases to clutch at itself. Thought follows thought without interruption, that is, without any need to divide itself from itself, so as to become its own object.”

So, meditation can allow us to stop “separating” ourselves from the rest of the world, from identifying ourselves as “other” from everything else. Liberation is precisely this “progressive disentanglement of the Self from every identification. It is to realize that I am not this body, these sensations, these feelings, these thoughts, this consciousness. The basic reality of my life is not any conceivable object”.

And so, by liberating oneself from the ego, one is also liberated from suffering, because the ego is the one that craves and clings to things in the material world. The “true self” behind the ego understands that it is part of a global consciousness and thus does not crave things for its own personal benefit – what would be the point of that? Craving and clinging, or trishna, is the cause of all suffering in Buddhism – that is the second Noble Truth. By meditating and focusing deeply on the breath, on sensations in the now, we eliminate the barriers between ourselves and the world and liberate ourselves from the ego, thus liberating ourselves from trishna. The only thing that matters in that moment is one’s true nature, which is pure consciousness without identification.

Today, we’re down to 9 men and 5 women. I notice a man who only appears at meal times, and never in the meditation hall. He is perpetually in a bad mood and looks like he doesn’t want to be here. He doesn’t attend chanting and morning Dhamma talks either. I wonder – what’s his story?

I struggle again with sitting meditation. I complete a round of walking and sitting, and then do a lying meditation. I have a few minutes before lunch, so I decide to do a loving kindness mediation. I think of the grumpy man and wish him well.

I realize it’s easier for me to keep my focus during walking meditation if I look at my feet rather than in front of me. It’s also easier when I keep my eyes open during the sitting meditation and fixate one object. I wonder if that’s a “weakness”? That I need my eyes in order to focus, that I am unable to be completely mindful and observe my body and thoughts without “using” something to look at.

1pm, daily report. While I wait for my turn, I eavesdrop on the reports of the other meditators. The monk instructs the old man to do 55 minutes of walking and 55 minutes of sitting meditations. WHAT? Is that going to be my fate on the last day?

I receive new instructions during my daily report. 25 minutes per round today. Walking steps are now divided into lifting (pause), moving (pause) and putting.

I do 4 rounds that afternoon, and meditate for over an hour for the first time. I struggle. My mind wanders a lot and my whole body hurts from the sitting meditations. But I feel proud for sitting through it and trying my best.

6pm, chanting: I’m starting to really enjoy the chants, and even memorised some. It’s the only time of the day where we get to use our voices. It’s a soothing form of meditation. After chants, the teacher tells us the purpose of mindfulness is not to “stop thinking” in everyday life, but to learn how to observe our thoughts and understand them. It makes it easier for us to recognise negative or hurtful thoughts, and choose not to continue these thoughts. We can learn how to detach ourselves from our thoughts, not identify with them, and not let them consume us. You are not your thoughts. Your thoughts are just “things”. Things you can let go of. Let go and come back to your body, to your breath.

The teacher keeps calling the retreat a “training”. I guess it really is one. This is hard work, much harder than I expected.

* * *

Hmm. I think… I had a little breakthrough tonight. I’ve been thinking a lot about dukkha and trishna, suffering and craving. The Buddha said our suffering comes from craving and clinging, from wanting what we don’t have, or more of what we already have. Craving material things, relationships, social status, a better job, a bigger house. The reason we suffer is that we are never satisfied with what we have, and always crave more.

“The Second Noble Truth relates to the cause of frustration, which is said to be trishna, clinging or grasping, based on avidya, which is ignorance or unconsciousness. Now, avidya is the formal opposite of awakening. It is the state of the mind when hypnotized or spellbound by maya (Maya in Buddhism is the world of facts and events, understood to be an illusion), so that it mistakes the abstract world of things and events for the concrete world of reality. At a still deeper level it is lack of self-knowledge, lack of the realization that all grasping turns out to be the futile effort to grasp oneself, or rather, to make life catch hold of itself. For to one who has self-knowledge, there is no duality between himself and the external world.”

I started wondering – what is it that I crave? What is my dukkha? What is it that makes me suffer? It took me a while to find the answer. I don’t really crave anything tangible. I don’t want more money, more things, more (or different) relationships, better conditions, a better status. While I meditate, my monkey mind never really wanders to people, or things I want that I don’t have, or pain from my past, or anything like that. Instead, all I’m thinking about is the things I want to create, the things I want to discover and see in this world, and wondering if I’m wasting my time right now, sitting here staring into space, instead of going out and doing that.

It hit me. What I constantly crave is new experiences, new information, new knowledge, new art, new everything. Whenever I choose to do something, I’m always wondering about the other things I’m missing out on. I’m the kind of person who starts 5 books at the same time, because I’m afraid I’m missing out on the one I didn’t choose first. The kind of person with 27 open tabs on my browser, because I’m afraid of missing out on all the information. The kind of person who wakes up before 6am because I’m afraid of wasting my time sleeping. The kind of person who’s terrified of dying without having created all the ideas in my head, read all the books, learned about every concept, discovered every culture, visited every country, lived every experience, felt every feeling. Maybe I should feel grateful that my cravings are not linked to material things, to relationships, to career or financial goals. That they’re rather tied to curiosity, to seeking new experiences, new knowledge. But that still makes me suffer. I know it’s the ego, craving, seeking all this. It’s not the “true self”. The “true self” behind the ego doesn’t seek anything. It just is. My true self cannot fully develop itself if my ego is always taking over, running around like a curious child on a sugar high, wanting to fulfil all its desires.

I’m very well aware that I cannot possibly explore or learn or see everything there is out there. No matter how much I create, how much I discover, how much I learn, there will always be more out there that I will want to seek. This causes me major anxiety. I’m terrified that I’ll never have enough of those intangible things and experiences. There will always be something “new” I want to explore. It just dwelled on me that perhaps something I considered to be a quality, my curiosity, could be the cause of my personal dukkha, my “unsatisfactoriness”.

So… how do I break out of this? How do I liberate myself from this type of suffering? I tried to ask myself (my true self, not the ego) a simple question: “What is your ultimate purpose?”. “To be the best person that I can be, so that I can be of service to the world”, I replied. “And will constantly seeking new things help you achieve this?”, I asked my true self again. “Maybe in some way? Since I am seeking new knowledge, therefore (possibly) new wisdom. But not completely…”, I replied. “So what is it that will help you be of service to the world?”, I asked again. “Becoming the most balanced person I can be”.

Yes. Being balanced, aware, present. To fully engage with the world just as it is, with the people in front of me, right here and now, with complete and total awareness. That is the biggest gift I can bring to others. My total and undivided attention. That’s where mindfulness meditation comes in. To help us become fully present, in the here and now.

I may never be truly liberated from those cravings. But with mindfulness, I can learn how to observe these thoughts and feelings when they arise, without judgement or comment, recognise them as “frustration” or “anxiety”, then gently let go of them and not let them consume me.

DAY 4: “I KNOW WE’RE NOT SUPPOSED TO TALK BUT…”

In today’s Dhamma talk, the monk introduced the concept of the inner theater: The most popular movie in a person’s life is their own “inner theater”, the story of their life that they tell themselves, in which they are the main actor. It’s easy to get lost in our inner theater, to keep re-running the sad and scary parts. The power of self-observation learned through Vipassana allows us to get out of the role of “actor” in this inner theater and observe it from the outside, as a by-stander, and eventually assume the role of the “director”. By observing our own body through meditation, we observe our feelings and thoughts as a by-stander and detach ourselves from this inner theater, from the ego. There is no more “I”. This is why during meditation, we are told to repeat “Standing, standing, standing”, and not “I’m standing, I’m standing, I’m standing”. Because we are observing the body from the outside, and removing the ego from it. I got the answer to the question I posed at the beginning of this journey: “how can I develop non-attachment towards my own body – a material thing – if I have to focus all my awareness on it and observe it for so long?”. The answer is this: by having no identification with the body. This process of “no identification” is also extended to thoughts and emotions. When we observe our thoughts and recognize certain emotions, we can train ourselves to not identify with them. For instance, if we feel sad, instead of labelling that emotion as “I’m sad”, we can simply label it as “Sadness”. The ego is completely removed from the emotion itself.

Since the graceful lady left, I naturally assume the role of the melancholic lady’s helper. I carry her cushions and chair whenever she needs. The graceful lady left before I got the chance to give her a drawing I made of her. Yes… I’ve been drawing. I’m cheating. My attempt at “doing nothing” and giving my creative energy a break has failed. But she inspired me, and I had to draw her. Maybe someday she’ll stumble on it and recognize herself. I don’t even know her, but I’ll miss her.

The melancholic lady sits outside by herself and stares at the trees a lot. She reminds me of my mom. My mom always says she used to be a tree in a past life. She would call the plants on our balcony her “sisters”.

I guess I have somewhat of a routine now. Wake up at 5, go to Dhamma talk, go back to my room and read until breakfast, meditate 2 hours, go back to my room and draw, lunch, report with the monk, meditate 2 hours, take a break, meditate 2 hours, go to chanting, meditate 2 hours, go to bed. I have memorised the timer sound of each meditator, and I recognize each of them by their shoes, when I see them at the doorstep before entering the dining or meditation halls. Their silent faces are now familiar to me, and they have become part of my life here. They each have their own unique aura that I cherish. Being around them makes me feel comfortable and safe. Whenever I get frustrated during my meditations because my mind is all over the place, I can look over at one of them. I see how calm and focused they are. I get inspired by their strength and keep trying.

While going back to my room after meditation, I hear footsteps behind me and see the melancholic lady coming down the stairs. Suddenly, I hear her voice. “I know we’re not supposed to talk but… you look like an angel” she says to me. I’m completely taken by surprise. All kinds of emotions come rushing through me. I don’t know what’s moving me more. Hearing her voice. Seeing her face so up-close for the first time. What she said. “Oh… thank you. You’re so sweet” I say to her. She smiles at me. Back in my room, I start to cry. I don’t know why. I wish I had hugged her, or said something more. It wasn’t enough. It meant more to me than what I said.

During afternoon meditation, I take a break and sit on the balcony. 3 other meditators are there. We all sit and observe the trees. As I fixate on the leaves dancing in the wind, for just a brief moment, an overwhelming sense of peace takes over my whole body. I feel so comfortable around these people that I don’t even know. I feel calm, too calm. I feel my body disintegrate into the stillness of the air. I feel strangely connected to the trees, to the sky, to the wind. I breathe deeply. I feel…high, very very high. What is this? Wait, is this what “no-self” feels like? My face hurts. I’ve been smiling this whole time.

I’m learning more about trishna and karma from the book. Our clinging and craving not only create dukkha – suffering – but also create the kind of karma that will create more suffering.

“Thus the desire for perfect control, of the environment and of oneself, is based on a profound mistrust of the controller. Avidya (ignorance) is the failure to see the basic self-contradiction of this position. From it therefore arises a futile grasping or controlling of life which is pure self-frustration, and the pattern of life which follows is the vicious circle which in Hinduism and Buddhism is called samsara, the Round of birth-and-death. The active principle of the Round is known as karma or “conditioned action”, action, that is, arising from a motive and seeking a result–the type of action which always requires the necessity for further action. Man is involved in karma when he interferes with the world in such a way that he is compelled to go on interfering, when the solution of a problem creates still more problems to be solved, when the control of one thing creates the need to control several others. Karma is thus the fate of everyone who “tries to be God.” He lays a trap for the world in which he himself gets caught”.

But I wonder… perhaps not all desires should necessarily be liberated from. Some desires are important to have. The desire to be a better person. The desire to help all living beings. Perhaps it is up to us to recognize which desires are simply feeding the ego, and which are helping the world outside of ourselves.

Today, I saw the grumpy man meditating! Did my loving kindness work?

Day 5: RISING, FALLING, SITTING

“True dhyana (meditation) is to realize that one’s own nature is like space, and that thoughts and sensations come and go in this “original mind” like birds through the sky, leaving no trace.”

The melancholic lady left today. I wonder where she went, what life she went back to. I wonder what this experience meant to her. I wonder if she benefited from it. I wonder if she’ll become less melancholic now.

The monkey mind is in full force this morning, but I push through and do 2 rounds of meditation. Sitting meditation gets easier, with the addition of the “sitting” step the monk told me to add yesterday, after “rising, falling”. In my mind, I draw a triangle from the top of my head to my knees, and try to keep my awareness inside the triangle. Rising, falling, sitting. Rising, falling, sitting. Sometimes, I get a minute or 2 of uninterrupted attention in which I feel completely immersed in a deep state of awareness – before the monkey mind makes his appearance again. I feel the energy inside the triangle, inside my hands and my knees, vibrating. The energy is all I can focus on. I forget myself. I forget the limits of my own body. I feel myself merging with the air around me. I feel high. I feel… empty. But full at the same time. Full of energy, full of light. Full of pure consciousness.

Then poof, monkey mind. Again. That bastard.

I wonder if that experience is Samadhi. That “one-pointed awareness” I read about in the book. It feels like that. The absence of differentiation between the knower, the knowing, and the known. The realisation that the ego is not real. The sense of “one-ness” with all beings, with the universal consciousness. This never happens to me during walking meditation, I wonder why. Perhaps because I’m still too distracted by the movement of my own feet that I’m unable to reach that state.

I befriended a pregnant stray cat. She comes around my room every day and keeps meowing until I come out and pet her. Today I caught myself having an imaginary conversation with her. Oh god, I’m losing my mind.

DAY 6: BUDDHA DAY

I miss human connection. Not talking, just.. connection. I find myself looking forward to meal times, not to eat but to sit with people and feel their presence next to me. I always try to make eye contact and smile to everyone I cross. The rock n’ roll couple and the nice man who looks at his feet always make eye contact. So does the old man. The new people however, they don’t even look up. A lot of them look sad or angry.

During Dhamma talk, the monk said something that stuck with me. While talking about observing thoughts and not identifying with them, he said: Anything that you can observe is NOT you. Your thoughts are not you, and you are not your thoughts. They are outside of you. They are separate. They are “other”. This is why he suggests to “label” thoughts and emotions by completely removing the ego from them. Call them “Sadness” or “anger” or “thinking”, rather than “I’m sad”, “I’m angry” or “I’m thinking”. Watch these thoughts without judgement or comment. Let them go, and come back to your breath. We cannot eradicate negative emotions or thoughts, he says. We can only choose not to continue them, not to engage in them, and let them go.

Whenever the monk talks about observing a thought or feeling, he always repeats its name 3 times. “Sadness, sadness, sadness”. And he puts up his hand in front of him like he’s holding a fragile ball, and with the other hand, strokes the imaginary ball like he’s caressing it gently, or petting a little furry animal. It makes it seem like he’s being kind to the emotion. I don’t know if he intends this to be interpreted that way, but I love seeing him do that. I like this image of being compassionate with our own feelings, and not judging ourselves for having them.

Today is Buddha day. We all go up to the main temple to attend the ceremony. Monks of all ages carry white flowers and walk in a line around the golden pagoda. Some of the meditators start talking to each other. I stay silent as I listen to some of their voices for the first time. It’s strange hearing them talk after all this time.

Back in the center, I try to meditate again. The sitting meditation keeps getting more and more complex with the added steps. In addition to “rising, falling, sitting”, there are now specific “points” on the body to focus on. Left knee, right knee, left hip, right hip. Walking meditation also gets more complex. The footsteps are broken down further and further, now into 4 separate movements.

During my loving kindness meditation, when I have to think of someone to give “love” to, I accidentally think of an animal instead of a person. I think of the pregnant cat.

DAY 7: LOVING KINDNESS

“This is why the Hindu-Buddhist insistence on the impermanence of the world is not the pessimistic and nihilistic doctrine which Western critics normally suppose it to be. Transitoriness is depressing only to the mind which insists upon trying to grasp. But to the mind which lets go and moves with the flow of change, which becomes, in Zen Buddhist imagery, like a ball in a mountain stream, the sense of transience or emptiness becomes a kind of ecstasy. This is perhaps why, in both East and West, impermanence is so often the theme of the most profound and moving poetry–so much so that the splendor of change shines through even when the poet seems to resent it the most.”

The rock n’ roll couple, the old man, and the nice man who watches his feet all left, and I’m officially one of the “old kids”. The only person still here from those I “met” on my first day is the man with the meow timer. Even people who came in after me are starting to leave, and some are even leaving before the end of the 4-day “minimum” period. I guess not everyone enjoys this.

The meditation hall has been quite empty for the past 2 days. A lot of the newcomers rarely come to meditate, I’m not sure why. I’m often alone here with the man with the meow timer. I admire him. He’s always here, always. He meditates for hours and hours on end, and looks very serious and diligent. He even eats very modestly, finishes his meal quickly, and goes straight back to meditation. I overheard him talking with the monk during his daily report. He has been here for a month. And he wants to stay longer and train to become a teacher.

I have more and more points to focus on in my sitting meditation today. Left knee, right knee, left hip, right hip, left ankle, right ankle. I keep messing up the sequence and have to repeat.

After chanting, the monk tells us the story of one of my favourite chants, “Jaya Mangala Gatha” – the Verses of the Buddha’s Auspicious Victories. It’s the story of the Buddha and the mad elephant Nalagiri. Nalagiri was a ferocious, enraged elephant feared by everyone. He belonged to the army of King Bimbisara. The Buddha, who had already been teaching for several years, had many followers and supporters. His two cousins, Ananda and Devadatta, were both his attendants and members of the Sangha – the community of monks. Devadatta became jealous of Buddha, and believed himself to be his equal. He asked the Buddha to give the community of the monks into his care, but the Buddha refused. Devadatta left, angry, and conspired with King Bimbisara’s son to bring about the death of the Buddha. They pricked and stabbed Nalagiri until he was mad with anger, and let him loose on the Buddha’s path. Nalagiri started charging towards the Buddha. People panicked and shouted and ran for their lives. The monks started warning the Buddha about the elephant coming in his direction, and begged him to change his path. But the Buddha smiled and told them to stand back. Ananda stepped in front of the Buddha to protect him, but the Buddha pushed him aside. “Do not fear” he said. Nalagiri kept charging, getting closer and closer to the Buddha. The Buddha called up the force of loving-kindness from deep within himself, radiating his boundless heart toward Nalagiri. “Nalagiri,” he said, “Come, my friend.” Like two waves meeting, the force of the Buddha’s loving-kindness collided with the moving mass of the raging elephant. Nalagiri slowed down and stopped, right in front of the Buddha. He bowed his head before him and knelt on the ground. Then he lifted his trunk and, forming a cup at the end of it, he scooped up a handful of dust from the road and sprinkled it on the Buddha’s bare feet. The Buddha reached forward with his right hand and laid it on the elephant’s forehead. “Nalagiri,” he said. “You are safe now, my friend”. The people cried, “It is a miracle! It is a miracle!” They tossed flowers and jewels and gems until Nalagiri’s massive shape was entirely covered. “Your new name, Nalagiri,” said the Buddha, “is Dhanapalako….Guardian of the Treasure. And the treasure, my friend, is your own loving heart.”

DAY 8: LETTER OF RECONCILIATION

Dear Body,

I’ve been observing you for 8 days now. There are no mirrors here, and I have not properly seen you in days. But you’ve been the center of my awareness. I haven’t been able to scrutinise your surface like I usually do, to pick out all your flaws and analyze them one by one and over and over. I’ve been watching you closely as you walk up and down this carpet over and over again, watching your feet lifting-moving-putting, watching your belly rise and fall and rise and fall.

Dear Body,

I didn’t know… that by simply letting me watch you like this, for hours every day, you would be teaching me to see my thoughts and feelings so clearly. To understand them, to accept them, to gently detach myself from them. It’s hard work, you know, observing you. You frustrate me sometimes. I fail, sometimes. But every time I’m done, there’s a warm, serene light that fills my mind and my soul, little by little.

Dear Body,

I’m sorry for all the years of pain and punishment I’ve inflicted on you. I’ve mistakenly identified myself with your surface, when you are so much more than that. I let the eyes of strangers on you dictate your worth, and mine. I tried so hard to control your shell and forgot your true purpose.

I was so harsh on you, Body, but you still did so much for me. You’ve kept me alive and healthy. You’ve stayed with me through it all. You didn’t break, when I tried so hard to break you. You almost broke that time, remember? But you came back, you got stronger, quietly. You held me, quietly. You kept loving me, quietly, when I hated you and couldn’t stand looking at you. You opened my eyes – our eyes – you tried to show me the truth. And now, you’re just letting me observe you, and teaching me about the mind, about emotions, about everything. You were always so much wiser than me, Body. I just never listened to you. How silly was I to think I could shut you up and control you.

Body, I’m letting go now. I won’t hurt you again, I promise. If you want to shrink or expand or age or change, I will let you, I won’t resist. You have an intelligence of your own that I will never be capable of understanding. I’m done controlling you. You are a miracle, Body, you are extraordinary!

But you are also impermanent. And I understand now that all this suffering was because of my attachment to you. Because I mistakenly thought that you and I were interchangeable.

I love you, for all that you do for me. But you are not me. You do not define me. You are a vessel, here in this moment and space. You are helping me walk on this carpet right now. You are helping me breathe right now.

Thank you for carrying my mind and my soul for a temporary moment here on earth. For being this marvelous, intricate, mind-blowing machine through which I can move in this world and try to fulfill my higher purpose.

I need you, Body, to fulfill all my dreams in this life. And I know you need me too.

I’m done fighting you, Body. I’m ready to listen to you now. You have so much more to teach me. And I can’t wait to hear it all.

With all my love,

N.

Here are some of the benefits I’ve noticed in my everyday life after Vipassana:

I am more mindful and self-aware, even when performing simple tasks.

I am able to observe my thoughts with detachment and neutrality.

I notice and appreciate simple mundane things.

I am more grounded and engaged in the present moment and the people around me.

I can stop myself from engaging in thoughts and feelings that do not serve me.

I am more compassionate towards others, specially when they are angry, sad, or experiencing any other negative emotion.

I can help others calm down when they’re stressed or anxious.

Even though I was always calm by nature and very rarely got angry or stressed, I am even calmer now, and listen more intently to others.

I understand myself and others better.

I am compassionate towards myself if I feel a negative emotion.

I am more focused on individual tasks.

I eat more mindfully, while practicing gratitude.

I have a healthier relationship with my body.

I feel more connected with nature.

I am very curious about Buddhism and other forms of spirituality, and dedicate a lot of my time to exploring them. This Vipassana retreat inscribes itself in the Theravada tradition of Buddhism. I want to learn more about Mahayana Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Zen Buddhism, Hinduism, and also different forms of meditation and mindfulness practices.

2 Comments

Each word from each recollection of your physical, mental, and emotional journey, served to both inspire and to calm. To fill me with energy, yet brought clarity. Already I feel myself healthier and more full of love, not even having had to experience it yet for myself. And I love you for all of the effort and craft that went into bringing this forward. I am excited for the work you’re doing here, and I feel blessed to have some insight to the journey along the way.

♥♥♥